I wrote about the AI PC concept back in December. The idea: a personal server that you own, running a codebase that your AI agents can connect to, edit, and serve from. An app that persists and grows with you as you use it.

Claude Code just shipped native SSH support in Desktop. So I spun up an EC2 instance and tested it. I wanted to see how close we are to making the AI PC real. The answer: closer than I expected.

The plan was simple. Compare two approaches side by side:

- Traditional SSH: Use Claude Code CLI locally and have it SSH into the server

- Native Desktop SSH: Use Claude Desktop's new built-in SSH feature, which runs Claude Code directly on the remote machine

I spun up a tiny EC2 instance, grabbed the SSH key, and started running through a checklist: CRUD operations on files, permissions, config files, file transfers, and eventually building and serving a web app.

The first thing I noticed when I told CLI Claude to SSH into the server is that it doesn't open an interactive session. It sends one-off commands. Every interaction looks like:

ssh -i key.pem ec2-user@3.84.197.88 "mkdir -p /home/ec2-user/docs && cat > /home/ec2-user/docs/01-attention-mechanism.md << 'DOCEOF'

# The Attention Mechanism

..."

Every file operation goes through the Bash tool. Claude can't use its native Read, Write, or Edit tools because those target the local filesystem. So it falls back to cat with heredocs for writes and reads. No structured diffs, no clean UI, just raw shell commands piped through SSH.

The permissions UX is also terrible. You're approving raw Bash commands, but you can't tell whether a cat is a read or a write. Claude suggested SSHFS as a workaround (mount the remote filesystem locally), but that doesn't give you a remote terminal, you have to set it up every time, and it'll never work on mobile. Dead end.

Traditional SSH confines the agent to shell scripting.

Then I connected through Claude Desktop's native SSH feature. Same permissioning prompts as local. Same tool suite:

- Read: native file reading, no

cat over SSH

- Edit: structured edits with diffs, no heredocs

- Write: clean file creation, same UI as local

It felt like working on my own machine, except the filesystem was on a server. One quirk: Desktop doesn't support ! bang commands like the CLI does, so everything has to go through the agent. Minor annoyance.

I added a CLAUDE.md on the server with instructions to talk like a pirate and set bypassPermissions in ~/.claude/settings.json. Fresh session: both worked. Pirate speak, zero permission prompts. Full yolo mode on a remote server.

But then I put my phone number in my local global ~/.claude/CLAUDE.md and asked SSH Claude if it knew it. Nope. Fully isolated. It doesn't see:

- Your local global

CLAUDE.md

- Your local skills

- Any local config whatsoever

Double-edged sword. You get full separation per server (different personality, tools, permissions for each), but if you've built up a library of custom skills locally, you'd need to recreate them on each server. No inheritance, no merging.

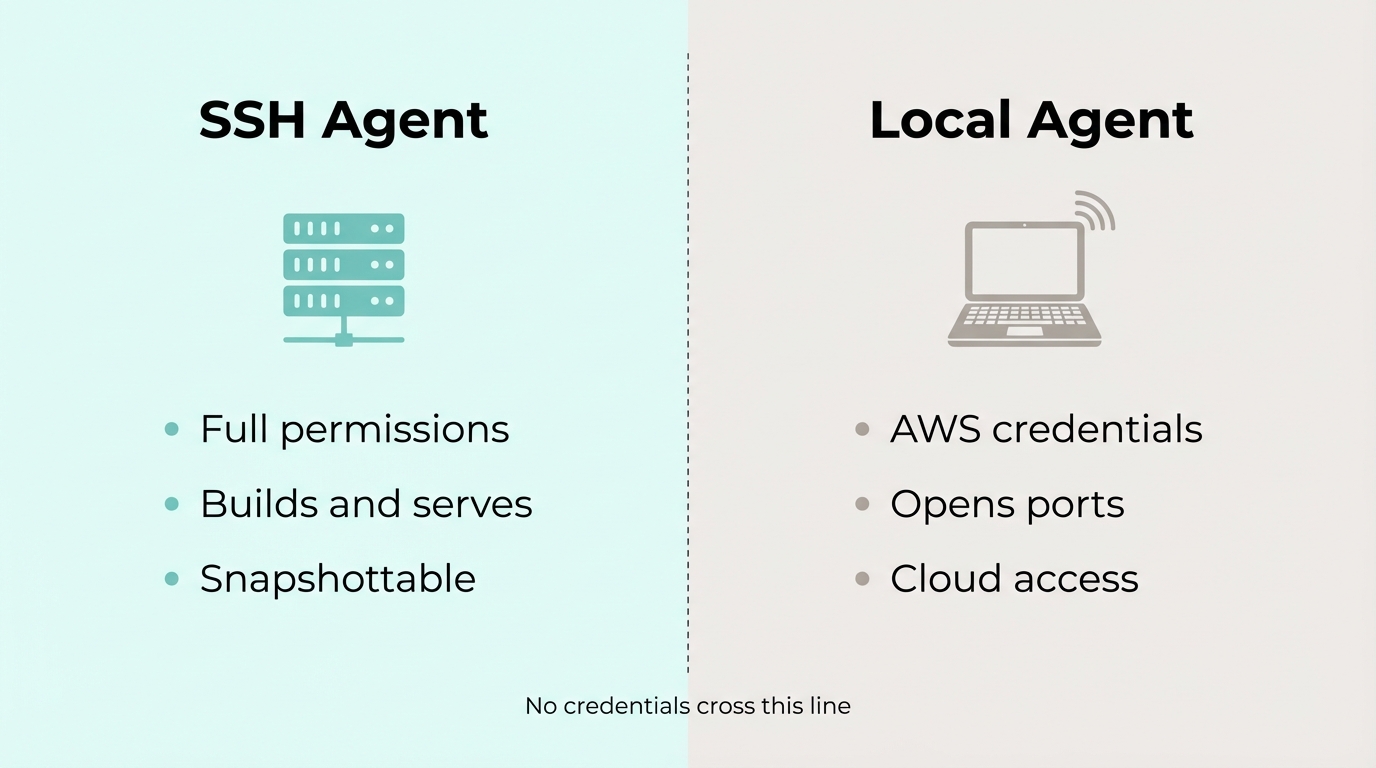

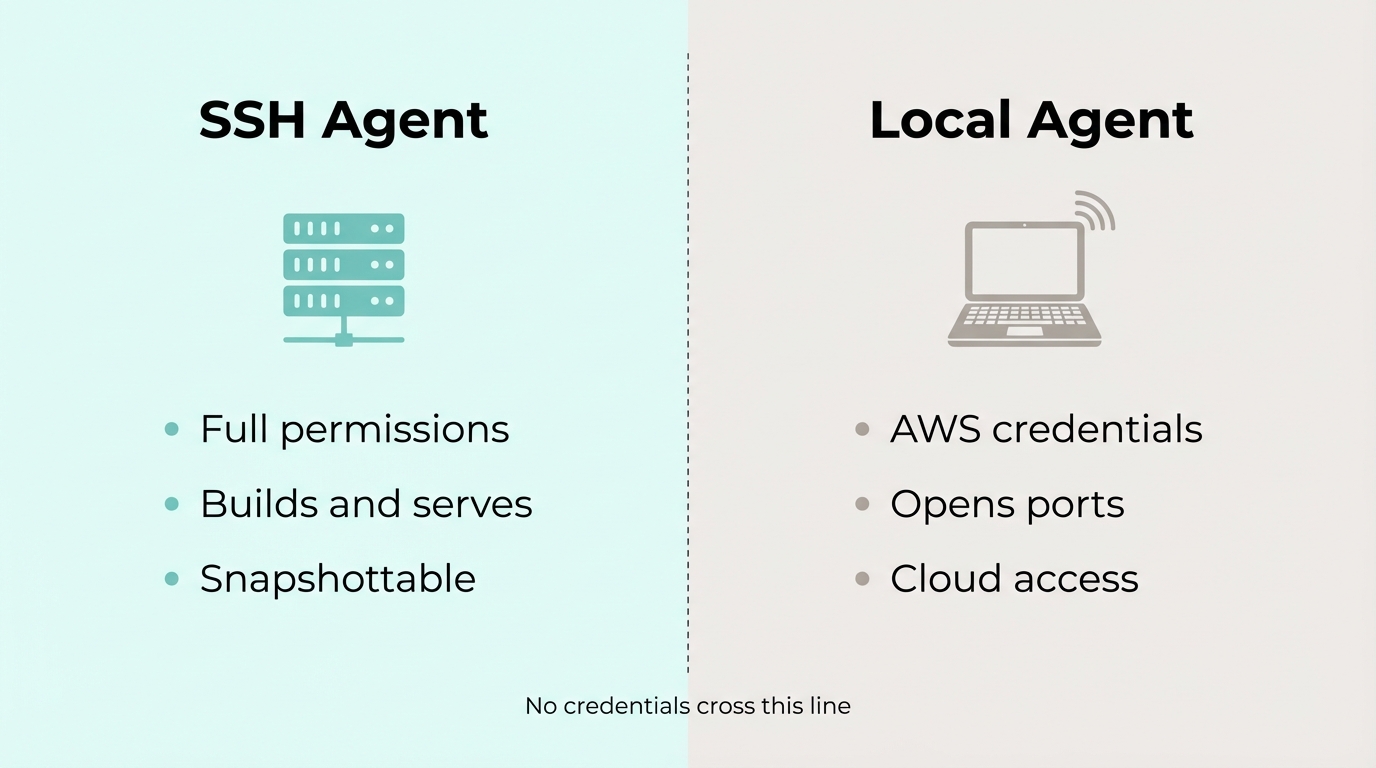

A disposable server is the perfect sandbox for an agent. Worst case, roll back to a snapshot. This is actually safer than giving an agent full permissions on your personal laptop.

- Conservative: Don't allow sudo. The agent can go wild with everything else.

- Full yolo: Allow sudo too, but snapshot first.

The boundary gets interesting when the agent needs cloud access. Yolo on a server is fine, the blast radius is one disposable box. Yolo with AWS credentials means the agent could spin up resources, delete things, rack up bills. Totally different risk profile.

So I split it: SSH Claude builds and serves, local Claude handles infra. Two agents, one trust boundary.

I told SSH Claude to set up a web app. When it needed port 80 opened, it told me. Local Claude handled that. Done.

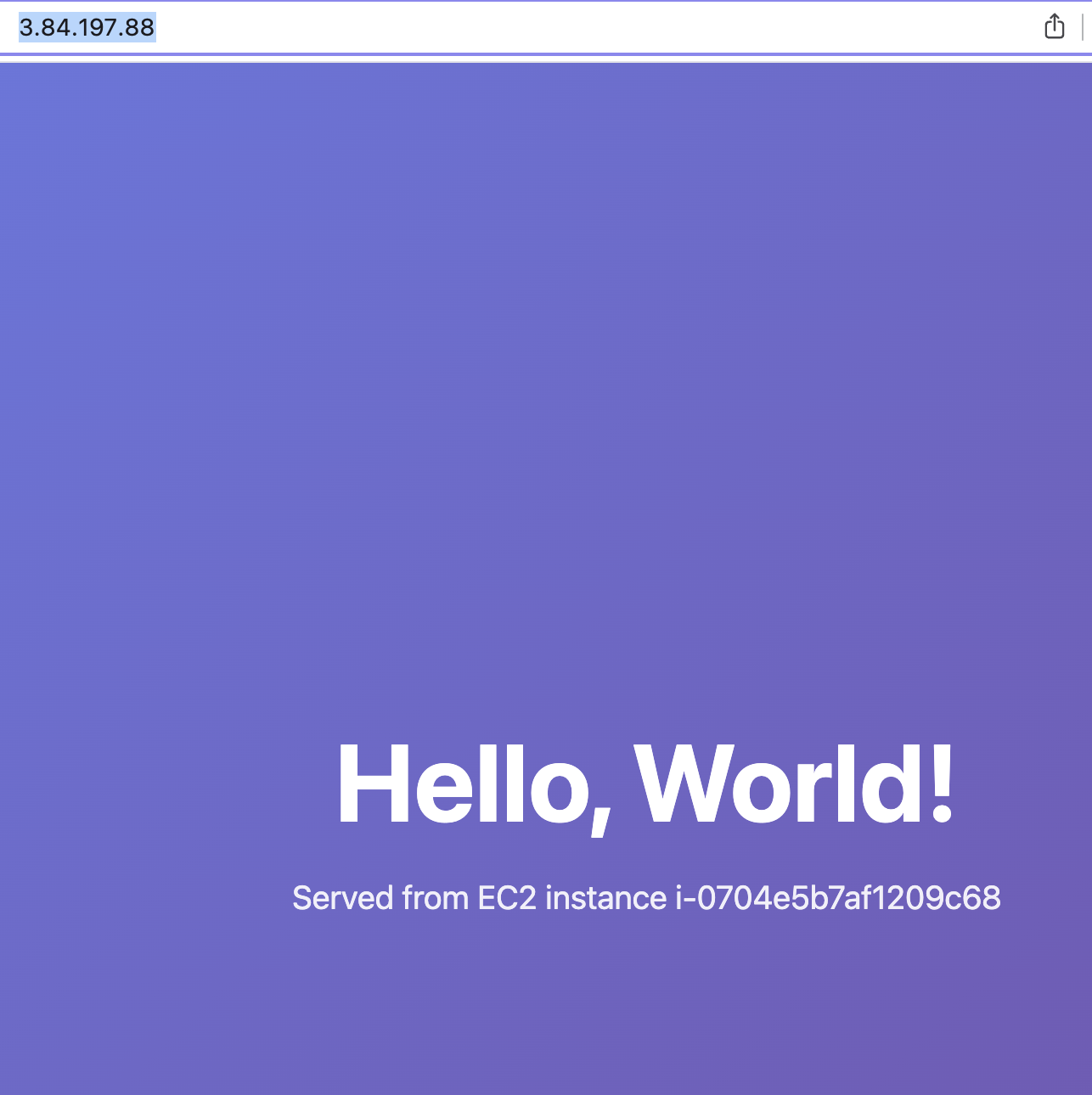

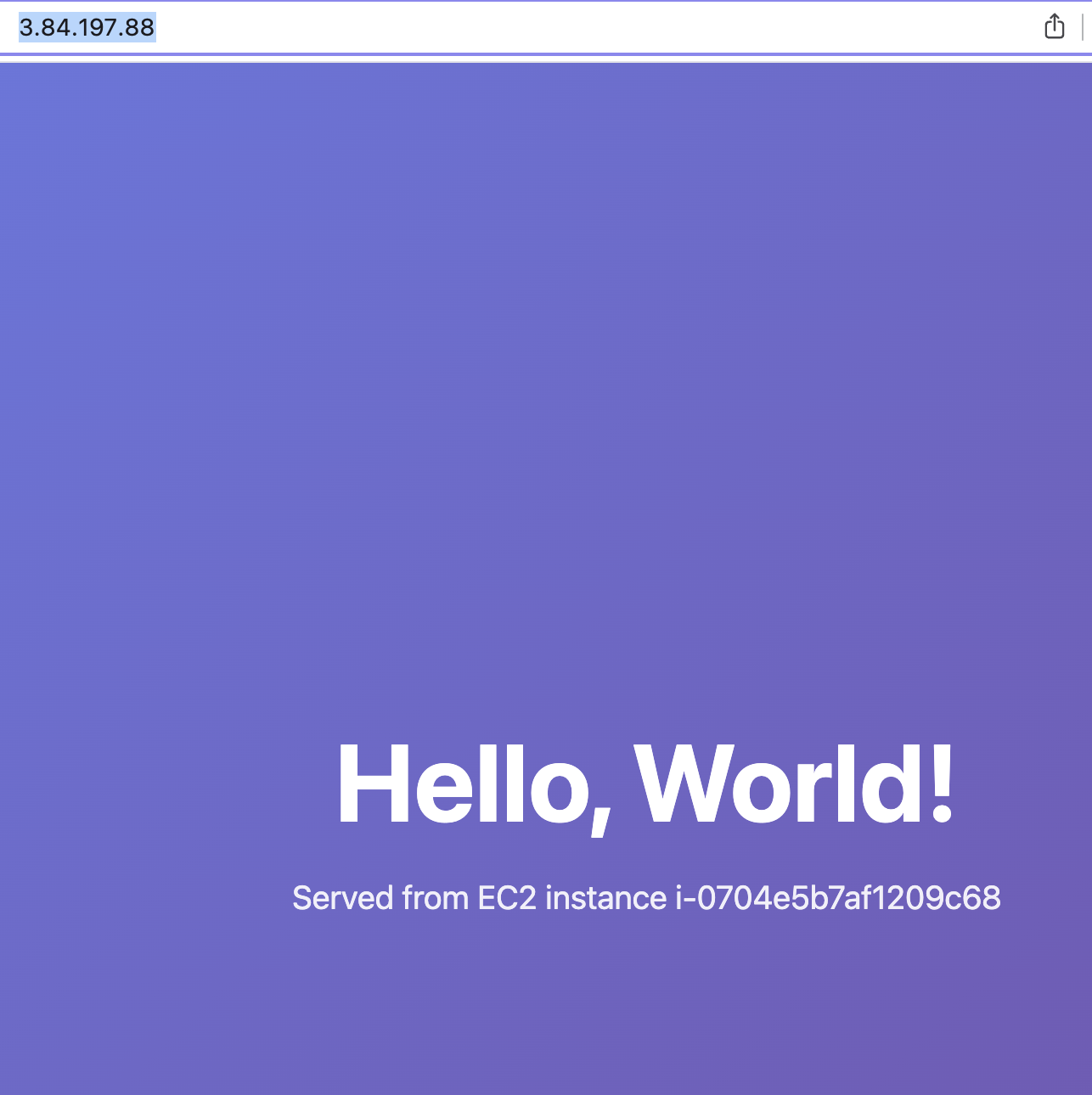

"Hello, World!" served live from the EC2 instance. No deploy pipeline. No git push. No CI/CD. The agent just... built it and served it.

To demo it, I opened the url on my phone, asked claude to the change colors and the message, and refreshed the page on my phone to see the changes instantly... The implications of this are huge.

This unlocks a type of app that's never existed before. An app where the developer and the user are the same person, and the app is always running while it's being built.

Think about what just happened with the demo. I was using the app on my phone. I thought of a change. I told the agent. The change was live in the app I was already looking at. No redeploy, no waiting, no switching contexts. The app and the development environment are the same thing.

And because it's your server, you can bring it anywhere. Claude connects to it today, Codex connects to it tomorrow. Switch providers whenever you want, the app and all your data comes with you.

Now scale that up. You upload your schedule, your resume, your contacts, all the stuff you currently track across five different apps and a notes folder. The agent turns it into a personal app, served from your server. Then your life changes. New job, new address, kid starts school. You tell Claude, and the app morphs a little bit more to what you need. It's a living thing that adapts because using it is the same as building it.

Building toward that next.